Note: PLOS issued the following press release on Tuesday, April 2nd. Brussels, Belgium, and San Francisco, United States – The Public Library…

A Dinosaur’s Journey to Publication

With yesterday’s publication of the paper describing and naming the dinosaur Dahalokely, one stage of a loooong research journey has reached its end. The details on the animal itself have been covered elsewhere, so this post focuses on the path of Dahalokely towards publication.

The fossils were first found in August 2007, and we presented a poster on the preliminary results at the 2009 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Bristol, England. I wrote an initial outline of the paper in October 2009, and started penning the preliminary text that same month. More bones were recovered in 2010, and by the summer of 2011, those fossils were completely prepared. The first solid draft of the manuscript was finished in September 2011, and co-author Joe Sertich and I sporadically bounced it back and forth for the next few months.

From the start, we knew that Dahalokely was something of fairly broad importance. Yes, it was a new dinosaur, but far more interesting was that it came from a poorly known time and place. Our initial phylogeny–based on all of the data available at the time–suggested that it was probably ancestral to later animals on Madagascar and India, a relationship never documented for any dinosaur before! As a consequence, we wanted to go for something of higher-than-average visibility.

Joe and I talked a fair bit about where to send the manuscript. One thing I was quite firm on was that, immediately or after a short delay, the paper had to be open access in some fashion; that is, freely available online at the journal website*. Our dinosaur was found in Madagascar, and I wanted people in Madagascar to be able to read it**. Also, we couldn’t afford to pay thousands of dollars to make the paper open access, as some journals require. This ruled out Nature*** as well as (sadly) some society journals that I really like otherwise. We thought the paper had a good shot at a place like Proceedings B (which opens its archives after a year), a journal with a broad readership and good reputation in the community. So, we formatted our manuscript accordingly and sent it off.

We submitted on April 12, 2012, and got the decision back on April 19. Our paper wasn’t of sufficient appeal for the journal’s general readership. We were a little surprised, because we thought we had fairly clearly laid out our case for broad interest in our cover letter and manuscript. But, this game is a bit of a lottery sometimes, so we went to the next journal.

Next, we then turned to PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America). The formatting requirements were almost identical, so it didn’t take long to turn around the manuscript. We sent it in on May 15, 2012, and got a decision back on May 23. Unsurprisingly by this point, it too was rejected without review, for similar reasons of not being of broad enough interest.

At this point, we were a little frustrated, and were done with playing the “potential impact” game. So, Joe and I elected to reformat for PLOS ONE, where the scientific soundness of the research alone matters, not its potential citability. This had an additional benefit of being able to move a bunch of supplementary information back into the main text where it belonged. Among other things, we pulled over the gorgeous photographic plates that Joe had assembled, as well as a bunch of the discussion on geology. Although the original manuscript plus supplementary information collectively formed a complete description, it is far better to be able to have all the good stuff in a single document.

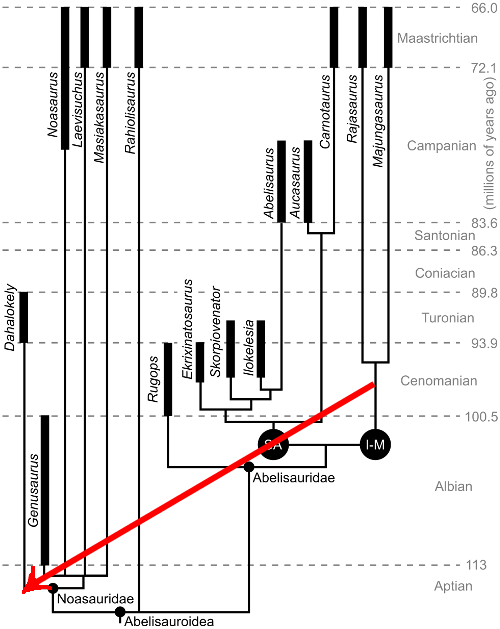

Then, something annoying happened. Our phylogenetic analyses up to that point had unequivocally placed Dahalokely as a member of Abelisauridae, and even more importantly as the earliest member of a group including only animals from India and Madagascar. This very, very nicely supported the hypothesis that Dahalokely was ancestral to later animals from both places.

<img class="size-full wp-image-875" alt="Our original hypothesis of the relationships of Dahalokely, showing it more closely related to other dinosaurs from India and Madagascar than those from anywhere else.” src=”https://theplosblog.plos.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2020/05/phylogeny_old.png” width=”362″ height=”589″> Our original hypothesis of the evolutionary relationships of Dahalokely, showing it more closely related to other dinosaurs from India and Madagascar than those from anywhere else.

While we were bouncing around other journals, our colleagues Diego Pol and Oliver Rauhut published a new animal called Eoabelisaurus. As the name (which means “dawn Abelisaurus“) implied, those authors hypothesized that the critter was the oldest known member of Abelisauridae by more than 40 million years. If we wanted our own paper to be complete, we had to throw Eoabelisaurus into our data matrix for phylogenetic analysis. How much harm could it do to our neat little hypothesis, right?

The results were annoying to the extreme. Thanks to the effects of Eoabelisaurus, Dahalokely was kicked out of the India-Madagascar abelisaurids, and placed at a most unsatisfactory position as a noasaurid. This poorly resolved group includes animals from all over the place (South America, India, and Madagascar), and now our poor fossils weren’t nearly as relevant for Madagascar itself.

As consolation, it was actually quite easy to place Dahalokely back as an Indo-Malagasy abelisaurid (one extra step, to use the technical lingo). We also could have fiddled with characters (i.e., adding features of dubious validity to the matrix) that would help move Dahalokely back where we “wanted” to see it. But, this would be a pretty weak way of doing things, and not exactly good science. We were stuck. The picture was now less clear, so we had to rewrite parts of the introduction and discussion, and reframe the description slightly to include broader anatomical comparisons. As something of more major interest, our new phylogeny showed fairly convincingly that Eoabelisaurus was probably not an abelisaurid. But, that is only tangential to our overall story.

Between the major reworking of the paper, a field season for both Joe and me, teaching obligations in the fall, and the arrival of a baby in my household, it took a few months to get our manuscript into shape for resubmission. We submitted to PLOS ONE on January 3, 2013, and got our initial decision (revise) on February 20.

The comments from the reviewers (Oliver Rauhut and Fernando Novas) were quite reasonable, and very helpful. Both Oliver and Fernando are unequivocal experts in abelisaurid dinosaurs and their close relatives, and have worked with a huge number of specimens, including some Joe and I haven’t seen in person. The reviewers pointed out a few features we originally thought were unique to Dahalokely that were actually found in some other theropods, so we revised our diagnosis and description accordingly. Another great suggestion was to move the geology section towards the front of the paper (rather than after the description), which we happily did. Finally, we added some extra labeling to the photographic plates, pointing out features that weren’t necessarily clear to a reader. We chose not to incorporate only a handful of minor suggestions (either because we had a different interpretation of a feature than the reviewer and consequently beefed up our text to explain things better, or because the suggestion seemed a little outside the scope of our paper). Overall, our manuscript was measurably improved by the peer review process.

It took us a few weeks to get everything into order, and we resubmitted the revised version on March 11. The notice of acceptance arrived on March 19–I definitely danced a little happy dance upon seeing that email. Later that day we got a request to fix a few little issues in the text prior to publication, which we did immediately. These final changes were accepted just a short two days after. The paper went live on the PLOS ONE website on April 18, less than a month after acceptance.

It was about a year from initial submission of the manuscript at one journal to publication at another. Most of the time wasn’t spent in review, but rather revision. In hindsight, the minor delay at the outset was actually a good thing, because it allowed us to incorporate important new data. Although PLOS ONE perhaps isn’t as fast as it was several years ago (higher volume of papers and all that), it was still only three and a half months from submission to publication, including a thorough review process. The editor (Richard Butler) and reviewers were pretty speedy, a major factor in this quick turnaround.

All told, I’m pretty proud of this paper. We have presented a fairly comprehensive description of an important new taxon, with detailed figures and measurements of every single known element. It’s a satisfying feeling.

*Yes, I know there is some hand-wringing about the definition of open access, and many (for good reason) say that open access under any model other than immediate CC-BY or BOAI is not really open access. Although I see some merits to this, particularly relating to text mining, I also think it distracts from the more immediate problem of just being able to read the darned literature. Personally, I don’t care what flavor of open access it is–I just want to be able to read it freely when and where I want.

**At least those with Internet access. This is an issue in its own right, unfortunately overshadowed by even bigger political, environmental, and social issues of more immediate concern. In any case, the university professors and students who would be most likely to have access to the article theoretically have better computer availability than your average Malagasy citizen.

***The snarkier side of me notes that the lack of feathers preserved with Dahalokely would hinder its chances at some journals to be left unnamed.

Citation

Farke, A. A., and J. J. W. Sertich. 2013. An abelisauroid theropod dinosaur from the Turonian of Madagascar. PLOS ONE 8(4): e62047. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062047

Full disclosure: Although I am a volunteer editor for PLOS ONE and a blogger at PLOS Blogs, I had no role in the editorial process related to my paper.