Access to raw scientific data enhances understanding, enables replication and reanalysis, and increases trust in published research. The vitality and utility of…

Developing an Ethic for Digital Fossils

Fossils are part of our planet’s natural heritage. These traces of organisms that lived long before the founding of any nation are essentially the only record of how we came to be. As such, the past few weeks have seen some controversy over the sale and attempted sale of some vertebrate fossils. Many (but not all) paleontologists charge that these sales create a private commodity out of a resource that should belong to all of us.

However, this argument about fossils as our planet’s natural heritage has stuck in my craw. Not because I support unfettered commercialization of fossils (I don’t), but because many paleontologists and many museums send very mixed messages. We say, “Fossils belong to the world!” Then we turn around and say, “But photographs and other digital representations belong to the museum.” As a result, it is nearly impossible for an individual paleontologist to easily and legally distribute digital photographs or 3D scans of fossils without a mountain of restrictions and caveats. In this post, I argue that we need a new and consistent ethic for digital fossils, one that better reflects the idea of fossils as planetary heritage.

Anyone who has done museum collections work knows about photography agreements. They’re those pieces of paper we never read and sign quickly so we can just get back to looking at fossils. These agreements generally say we’re allowed to take photos and use them for research and personal reference, but agree to not exploit them commercially or do other crass things with them. Examples of photography agreements are actually difficult beasts to find online, but for some examples check out the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology policy, or the policy from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (pdf). Quoting from one, “The MCZ retains the copyright…to the image of any museum owned material.” Wait….what?!!

Usage restrictions for images of museum specimens are not unusual, and in some cases even somewhat understandable, but what do these restrictions say about the museum specimens? It’s pretty simple–these restrictions imply that museum specimens are not the world’s heritage, but the property of an institution. On the one hand, considering fossils as “museum property” makes sense from an insurance perspective and in emphasizing that a museum is responsible for specimen care. However, I argue this is not consistent with an ethic of fossils as global heritage.

If fossils are indeed part of our planet’s natural heritage, we need to start treating them this way. Not just by preserving fossils from mishandling, theft, and breakage, or by protecting field localities from unauthorized collecting, but by opening up digital access to every single person on the planet. We can’t have it both ways, by claiming fossils as planetary heritage on one hand and unduly regulating images of this heritage on the other.

I envision a world in which researchers and the public alike are allowed and even encouraged to post digital representations of fossil specimens, with minimal restrictions. This is not to say that all of those who create photographs or digital replicas of specimens should be forced to share them (except for cases where data sharing is necessary). Unless otherwise requested as a condition of specimen access or unless the data go into a publication, the person who gathers the data should be free to do with them as he or she pleases. It is just unethical for research museums to prevent those who want to distribute representations of fossil specimens to do so. I have a massive personal database of specimen photographs and CT scans–but as near as I can tell, I am virtually prohibited from posting many of them freely (e.g., high resolution, CC-BY license or public domain dedication) without extensive negotations (if I’m lucky), because there is a chance that someone else might use them for “unauthorized purposes”.

I have discussed this issue a few times with many colleagues, and inevitably they raise a few standard objections.

“If digital copies are available, why would people want to come to the museum to see the original?” Ask the Louvre. Ask the American Museum of Natural History. I could have a whole house full of copies of museum specimens, but at the end of the day this just makes me that much more interested in seeing the originals. The originals are interesting because they are the originals! This is what drives the commercial fossil trade, and this is what keeps visitors streaming through the doors of museums. (thanks to Heinrich Mallison for articulating this response to me so well in a conversation at the most recent SVP meeting)

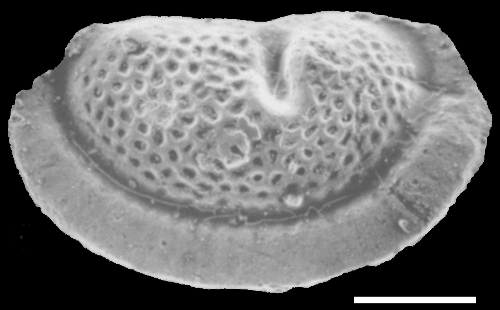

“If anyone can do anything with images and scans of fossils, won’t museums lose out on revenue? This revenue helps museums pay for preservation of their collections!” This argument is seductive and not without its merits. Museums do need money, after all! However, it is flawed in two aspects. First and foremost, the vast majority of images and digital scans of the vast majority of fossils at the vast majority of museums have little if any potential for revenue generation (unless there is a sudden demand for high resolution photographs of partial horse teeth in orthogonal occlusal and lateral views). These 99.99% of specimens are effectively being held hostage in hopes that the remaining 0.01% will generate some money for the museum. Second, there is nothing saying that museums cannot generate money from casts or their own artistic photographic databases. A museum is not obligated to release its own photos or allow anyone to use its own molds, but neither should it restrict distribution of the products of (non-damaging) photography and digitization by others. Similarly, museums should have the right to be compensated reasonably for facility use. It costs money to keep the lights on and takes valuable staff hours to shepherd photographers. But once the photos or scans are taken of objects that belong to the world, how can a museum ethically dictate use of these images?

“But won’t someone make a [creationist textbook / pornographic film / action figure] of our fossils that will make the museum and the science look bad?” As already noted, the great majority of fossils (and images of fossils) are virtually useless from the perspective of commercial reproduction. There is thus little reason to clamp down on everything in the pursuit of control over a handful of potentially annoying cases.

Furthermore, you can already find images of specimens or casts of specimens from many major museums in just about any unsavory context. This includes specimens originally from the collections of the American Museum of Natural History on the cover of creationist treatises or casts of fossils originally from other major museums photographed in situations of exceptionally poor taste (I am not linking to those here, for reasons that are hopefully obvious). I severely doubt that the museums have the time or need to clamp down on such uses of images of “their” fossils.

One potential problem, of course, is that image credits may be seen by some as endorsements. For instance, the license associated with a CC-BY figure from a PLoS ONE paper means that anyone can reuse it provided the original authors are credited. So, this means that a figure from Farke & Sertich 2013 could appear in a creationist textbook alongside text that claims falsehoods about the age of fossils, along with an image credit to “Andrew A. Farke and Joseph J. W. Sertich”. Although I obviously wouldn’t like this use of the image, I also think you’d have to be a real idiot to think that reproduction with credit for the source implies endorsement. Not to mention the fact that someone who wants to dig deeper will end up at the original research paper with its valid information. Is it any different from a right-wing or left-wing website quoting Shakespeare with attribution? And, do we really want to go down the road of deciding who should and shouldn’t be allowed to use fossils that are part of the world’s heritage? Such logic bites both ways. Is this really much different from denying specimen access to a research rival?

“If you just ask the museums, they’ll let you post the images under your desired license.” This may be the case for some museums, but it represents both an unwieldy step (particularly for large data sets) as well as an opportunity for unnecessary red tape and stalling by institutions. I would far prefer to see permission to do such things granted at the time of photography or scanning. Some might also argue that these rights are already granted when museums allow photography for research–however, I am not so sure on this from the agreements I have read.

“Museums need to be able to track usage of their specimens.” This is an excuse for limiting digital distribution of fossil data, but it is not a reason. Thanks to the magic of metadata and search engines, it is actually possible to find out who is mentioning certain specimens (for instance, there are 281 mentions of AMNH 5244, a Montanaceratops braincase, according to a Google search, and around 40 mentions in the scientific literature according to Google Scholar). A search for “Tyrannosaurus” brings up images that can be fairly easily matched to relevant museums. It isn’t difficult, and it especially isn’t difficult today.

First, Do No Harm

A museum’s responsibility with a fossil collection is to preserve the specimens for research, education, and exhibit. This is exactly why most fossils are kept behind locked doors under climate-controlled conditions, why sensitive locality data are not disseminated, and why trained museum personnel are the ones who (should generally) make decisions about procedures that may affect fossils. Museums may reasonably restrict photography and scanning if an unpublished specimen is under active study, or they may restrict handling and transport if these activities unduly risk damage to the fossil. However, once the photography or other imaging is cleared from the perspective of specimen safety, there is little reason not to allow unfettered use of the imagery. This does not harm the physical specimen, and arguably it reduces the need for handling of the specimen while increasing usage of the specimen–a long-term good. And as mentioned above, if fossils belong to the world, why should museums restrict distribution of various representations of fossils?

The Barn Door is Already Open

Another reality is that “unauthorized” use of images of specimens from museum collections is already rampant. A quick search on CafePress turns up all sorts of fossils on t-shirts and mouse pads that are almost certainly not expressly permitted by the museums. Thingiverse has (almost certainly unauthorized) printable 3D models of fossils on exhibit at major museums. Wikipedia articles are populated by photos of exhibit specimens, many taken without “proper” authorization or distributed under inappropriate licenses according to a strict reading of many museum public photography policies.

These uses may technically be unauthorized in many cases, but in nearly every single instance they are beneficial to museums and beneficial to paleontology as a field. Digital reproductions allow the public to engage with fossils in a way they might not get to otherwise. Digital photos allow the public and researchers alike to access fossils they might not have physical access to. Photos and CT scans reduce handling of delicate specimens, facilitating specimen conservation. Slapping unnecessary copyrights and restrictions on distribution of images does not help. At best, this provides an artifical sense of security, and at worst it discourages researchers from sharing their data. It certainly has discouraged me from sharing mine.

And let’s not forget…when scientists sign over copyright for their research papers to publishers, the museums that house the specimens will never see a single penny. An image in Cretaceous Research will return profits to the shareholders of Elsevier, but none of these profits revert to the institution (or the researcher). The revenue from an article describing a new species and published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology will support the activities of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (a worthy cause), but nothing will be returned to the museum for the care of that specimen. A paper with a figure of a dinosaur skull on the PLoS ONE website generates ad revenue for long-term maintenance of the journal, but nothing to pay for conservation materials to stabilize the fossil. Somewhat ridiculously, most museums (and paleontologists) have no problem with this but would be annoyed if I created a personal website that distributed my personal photos of these same specimens under a public domain dedication.

During a time when museums and science are under fire from nearly every financial and political quarter, do we really need another way to reduce access to museum specimens and fuel critics who deride “elitism” in our scientific, educational, and cultural institutions? If public museums want to distinguish themselves from the dreaded privately owned collection in someone’s summer cottage, make the imagery and scans of public fossils as public as possible! Cut out the caveats and restrictions that imply fossils are private property.

In the end, I understand why museums and paleontologists want some control over images and 3D scans of fossils. It’s a scary world out there. We need and have to abide by the regulations in place right now. But, fossils belong to the world. We can’t have it both ways. Let the world distribute and access fossil imagery.

Summary

- If paleontologists and museums claim that fossils are part of the world’s heritage, unnecessarily restricting distribution of and access to digital representations of these specimens conflicts with an ethic of fossils as world heritage.

- Museums and paleontologists need to develop an ethic for reproduction and distribution of fossil specimen imagery that ensures access to the greatest number of people with the fewest restrictions.

- Even if researchers and members of the public with digital images and scans shouldn’t be required to share their data, they should be allowed to do so under a license of their choosing.

Closing Note: This is probably a provocative article for many, but I think the field of paleontology needs to wrestle more deeply with what it means for fossils to be “natural heritage” in the “public trust” (to borrow terms from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s ethics statement). Have we gotten so wrapped up in the idea of copyright and museum property that we have lost sight of what it means for something to be a scientific and global resource? Is there still a place for museums to claim copyright on fossils where legally allowed? I’ve certainly been doing a lot of thinking about it lately, and encourage a discussion in the comments section. Opinions presented here are my own and are evolving.