Shake Your Tail Bone! (and shape your skeleton, if you’re a bird)

Those poor tail bones, always getting shortened and lost during the course of evolution. A long tail is the default condition for four-limbed vertebrates, but this tail disappears with shocking regularity. Frogs ditched theirs early in their evolutionary history. Humans and other apes did the same. And, of course, birds.

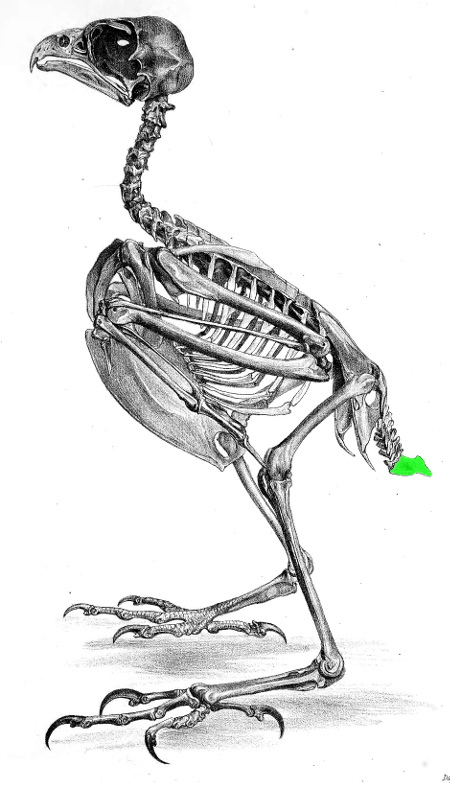

Well, perhaps disappear isn’t quite the right word for what happened in these groups. The tail is still there–just with many fewer vertebrae. Those of us who have carved up a turkey or chicken don’t pay much attention to their pitiful tails. It’s a fatty little nub, without much in the way of meat, bound for making soup stock. If you’re weird like me (when I was 12 or so, I cleaned and mounted the bones of our Thanksgiving turkey), you might have picked apart the tail and noticed a few things. First, the bones are pretty simple…most of the vertebrae behind the hip are short and squat. But most intriguingly, the last little chunk of tail is particularly weird: a flattened mass of bones, formed from several vertebrae fused together. The technical term for this structure is a pygostyle.

Even though the pygostyle is a pitiful-looking bone, it (and its surrounding tissues) are important for anchoring the spectacular tail feathers of many birds. In turn, these tail feathers are shaped in part by how birds use these tails–whether in slow soaring flight, rapid plunges through the air, or long aquatic dives in pursuit of fish. A close relationship between the anatomy of the wing bones and locomotion style has been documented in many bird groups–after all, the wings are the obvious system to investigate for birds. But do the same relationships between locomotion and bony anatomy apply to the tail?

Ryan Felice, a Ph.D. student at Ohio University, and Pat O’Connor, Ryan’s graduate advisor, documented shapes and sizes for the loose tail vertebrae and pygostyles from 51 species representing a variety of waterbirds and shorebirds. The sample included everything from loons to penguins to storks to seagulls, spanning a variety of body sizes and locomotion styles. So, what did the researchers find?

It turns out that pygostyle shape is closely related to foraging style–birds that forage underwater, such as penguins, have a shape that is quite different from that seen in birds that forage from the air. And similar shapes appear convergently in evolutionarily distant lineages. Penguins, puffins, and boobies are separated by at least 60 million years of evolution, but all have a long and straight pygostyle. They also all chase after their prey underwater.

So why these convergences? Felice and O’Connor suggest that underwater locomotion has a unique set of demands on the skeleton from aerial locomotion, perhaps related to particular patterns of muscle development or to resist forces applied to the skeleton when using the tail as an underwater rudder. Or, it might have something to do with the orientation of the tail feathers in diving birds (more research is required on this latter point).

The new study, published last week in PLoS ONE, documents yet another way that bird skeletons reflect their lifestyles. From a paleontological perspective, the work will hopefully open another path to infer the behavior of fossil species. So the next time you see that pygostyle on a bird, make sure to say thank you for being such a nifty feature!

Want to learn more? Read the paper in PLoS ONE!

Felice RN, O’Connor PM (2014) Ecology and caudal skeletal morphology in birds: the convergent evolution of pygostyle shape in underwater foraging taxa. PLoS ONE 9(2): e89737. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089