Baby moa bones: more than meets the eye

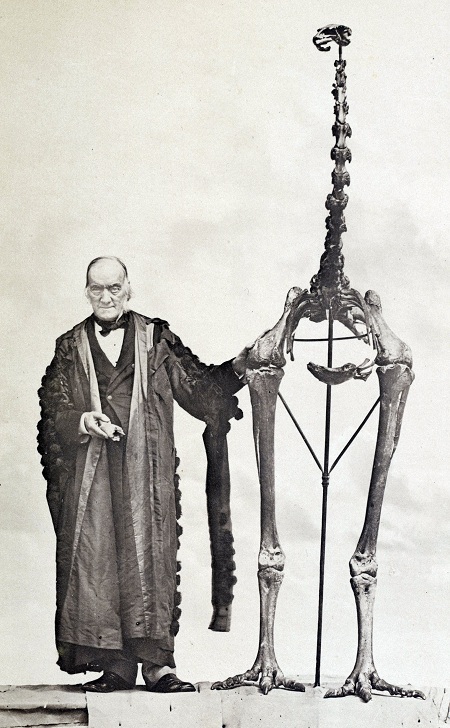

The name “moa” inevitably conjures up pictures of giant, lumbering bird-beasts, destined for extinction at the hands of humans. For fans of paleontological history, we usually recollect the grumpy looking Victorian era paleontologist Richard Owen, dwarfed by a mounted moa skeleton. Yet, this rather monotone popular conception itself is dwarfed by the true diversity of the fossil record.

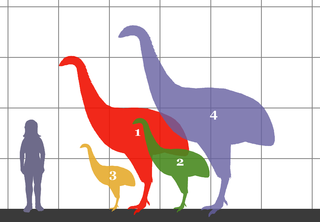

Moas–members of the family Dinornithidae–were a group of flightless birds native to New Zealand. Although the number of recognized species has fluctuated as information on genetic, age-related, and sex-related differences trickle in, they were clearly a pretty diverse lot. The smallest were around 20 kg in adult body mass, roughly the same size as a modern rhea, and the biggest topped an estimated 200 kg, nearly twice the size of an adult ostrich. Most of the species have an excellent fossil record, including isolated bones, associated skeletons, naturally mummified body parts, and dried-out dung. Along with these remains are many bones of small, presumably young, moas. But what species are they?

By being able to match young moas (“mini-moas”, if you will) to their corresponding adults, scientists can learn a whole bunch about the diversification and ecology of the group. Did moa species achieve different sizes by extending their growth phase, or growing more quickly over the same amount of time, or starting out at different sizes, or some combination? Did moa habits change over their lifetime?

Adult moas are fairly easy to tell apart, but moa chicks are another story altogether. The bones of young moas were not yet completely developed, so many characteristics used to distinguish species were absent. This is a pretty common problem across extinct animals and can be solved in a few different ways. If you only have one species of an animal in a rock of a given age, it’s probably a safe bet that any baby animals you find go with the adults. Things are complicated when you have multiple closely related species living in roughly the same place, as happens with moas in New Zealand. For extinct dinosaurs such as Centrosaurus, this can be solved by looking for localized fossil beds where only one species predominates, often representing a group killed in a single event. We don’t have such a luxury with moas, as far as I know, so it’s necessary to get a little creative.

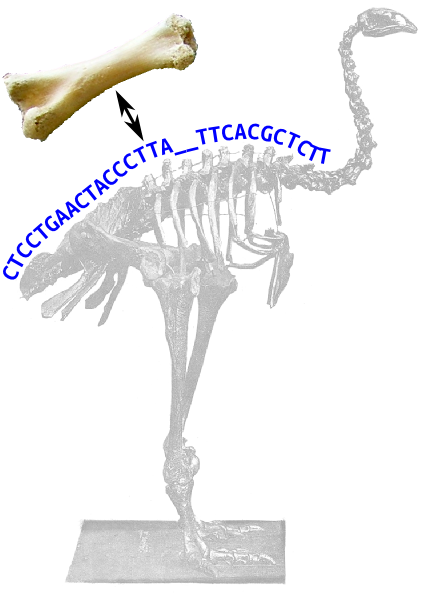

Because moas went extinct relatively recently, extraction of their ancient DNA is quite feasible with modern technology. If you have DNA from samples for which the species is known, you can then use that DNA sequence to identify unknown samples. Leon Huynen and colleagues recovered DNA from 29 different baby moa bones–nearly all of which had never been identified to species before. Unique sequences for each species allowed a confident match between young and old.

The DNA work is cool enough in its own right, but it was only the beginning for the research team. Three-quarters of the identified specimens belonged to the coastal moa, Euryapteryx curtus. Some discussion has focused on how many subspecies the known fossils represent, based on evidence from DNA, bone anatomy, and growth rates. The DNA suggested that two forms are within the sample (represented by slightly different sequences), consistent with previous DNA work as well as their geographic separation.

Intriguingly, the shapes of the thigh bones measured for this study were fairly consistent across individuals of the same size for most of the species sampled. This indicates that any major changes in proportions didn’t show up until later in growth; a bigger sample will certainly help sort out these sorts of developmental and evolutionary questions.

The research, published last week in PLOS ONE, provides some important results–verifying the first bones from moa chicks of particular species, supporting additional hypothesized moa subspecies, and providing information on bone development in an extinct animal. With bigger samples from a broader range of specimens, there will be much to learn about how this surprisingly diverse group of birds grew. Some previous workers have speculated that the apparently slow growth and reproduction rates of moas doomed them to extinction at the hands of humans. Future studies on moa chicks, adolescents, and adults, will undoubtedly refine this picture.

Citation

Huynen L, Gill BJ, Doyle A, Millar CD, Lambert DM (2014) Identification, classification, and growth of moa chicks (Aves: Dinornithiformes) from the genus Euryapteryx. PLoS ONE 9(6): e99929. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099929. [open access]