Romer’s Gap and the Four-Limbed Critters of Nova Scotia

The fossil record is a window into the past, but much of that window is boarded over. This situation spurs paleontologists to look in new places and new rocks, in an attempt to pry some of those boards off that window into our planet’s history. This is a great example of how paleontology is a testable science. Missing fossils from a certain time span? Look in rocks from that time span, and you should find them!

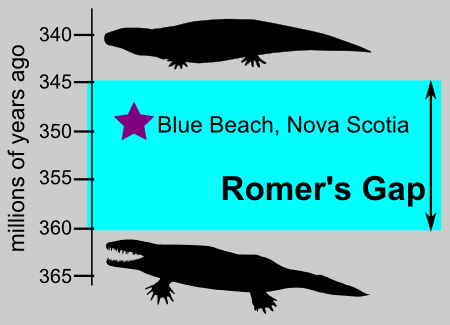

“Romer’s Gap” presents a classic case of the incomplete fossil record. We know quite reliably that tetrapods–the four-limbed vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, and us–originated around 370 million years ago. Fossils from 365 million years ago show distinct arms, legs, fingers, and toes on animals such as Acanthostega, leaving no doubt as to their tetrapod status. And we also know that tetrapods were pretty successful after that, because I’m using my tetrapod forelimbs (arms, hands, and fingers) to type out this blog post. But frustratingly, a time slice from around 360 to 345 million years ago yields precious few tetrapod fossils. This phenomenon was first noted by paleontologist Al Romer, hence its nickname of “Romer’s Gap“. The gap frustrates scientists because it is so soon after the origin of tetrapods, immediately before many important groups appear in the fossil record. That interval probably includes many events central for the transformation of tetrapods from leggy fish into truly terrestrial organisms. Tetrapods must have been around during Romer’s Gap, but where were they?

Eoherpeton at top modified from original by Nobu Tamura (CC-BY). Ichthyostega at bottom modified from public domain original by Scott Hartman, phylopic.org.

Various ideas have been proposed to explain the gap. Two front runners include:

- Low atmospheric oxygen levels put a damper on land animals. No oxygen, no animals. But, it turns out that oxygen wasn’t that much lower than other times in history, and were actually higher than times just before the “gap”. Furthermore, marine waters should have had even lower oxygen (long story–I’ll just wave my hands and say “Chemistry!”), providing extra pressure for tetrapods to move onto land.

- Artifact of collection and/or preservation. Is there a genuine gap in the fossil record? For any number of reasons, the fossil record is patchy. You might not have rocks from the type of environments to preserve particular organisms, or paleontologists just haven’t gotten around to studying the appropriate rocks yet.

As more paleontologists seek out more fossils, the latter hypothesis is starting to gain ground. A new study by Jason Anderson and colleagues, just published in PLOS ONE, provides additional support along these lines.

Blue Beach, rimming an estuary on the Bay of Fundy, has a long history of producing fossils from the time span including the base of Romer’s Gap. But, these rocks are notoriously hard to work. Wide swings in tidal levels limit working time to only a few hours a day, and most fossils are isolated bones difficult to assign to a particular kind of animal. Unless the finds are collected soon after exposure, they are lost to wave action. Thankfully, discoveries by local amateur paleontologists, in concert with fieldwork by external researchers, have slowly and steadily produced a stream of fossils.

The fossils described in the new study are nearly all isolated bones–individual limb, pelvic, and shoulder girdle pieces. But, by comparing them to more complete finds from elsewhere, it is possible to identify the specimens to varying degrees of precision.

Let’s face it–the limb bones of early tetrapods are pretty clunky objects, lacking the sweeping and elegant lines of today’s salamanders, lizards, or mammals. The above image is a great example of a typical early tetrapod arm bone. But, each awkward ridge and bump points to the bone’s original owner. For instance, the bone shown here is similar to that of an animal called Pederpes, which belongs to a family of early tetrapods called Whatcheeriidae. Imagine something that looked like an ugly salamander, and you’ve got Pederpes.

All together, 37 different specimens (including isolated limb bones, skull bones, and even a handful of specimens with multiple bones from the same individual) were studied by Anderson and colleagues. The fossils could be referred to six or seven different groups of early tetrapods, showing that tetrapods were going strong even in the middle of Romer’s Gap. Some of these (closely related to Ichthyostega, shown below) are forms that are most closely associated with earlier times in earth’s history; one way or another, they made it through a big extinction just prior to Romer’s Gap. Maybe, then, the extinction didn’t hit tetrapods as hard as previously thought.

Blue Beach isn’t the only locality to plug Romer’s Gap–another recently described set of fossils from Scotland shows a similarly rich tetrapod ecosystem. Together, these localities in disparate parts of the world suggests that the purported gap in the fossil record is more a collecting artifact than the result of genuine rarity of these animals during their time. Anderson and colleagues perhaps summarize it best:

“It now seems that, whenever we discover rare windows into this time period, we find numerous fossil tetrapods reflecting a rich diversity of forms.” — Anderson et al. 2015

In other words, Romer’s Gap probably isn’t a real phenomenon! With more fossils, it’s getting shorter and shorter. This is so often the case in paleontology–and that’s a good part of what keeps us all out looking for fossils. A “gap” in the fossil record is just a challenge to overcome.

Citation

Anderson JS, Smithson T, Mansky CF, Meyer T, Clack J (2015) A diverse tetrapod fauna at the base of ‘Romer’s Gap’. PLOS ONE 10(4): e0125446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125446