My vision for this journal is to create the richest community possible around emerging tools and techniques that will shape the future of our world…

Rethinking Research Assessment: Addressing Institutional Biases in Review, Promotion, and Tenure Decision-Making (part III)

Authors: Ruth Schmidt is an Associate Professor at IIT’s Institute of Design and Anna Hatch is the program director for DORA. PLOS supports DORA financially via organizational membership, and PLOS is represented on the steering committee of DORA.

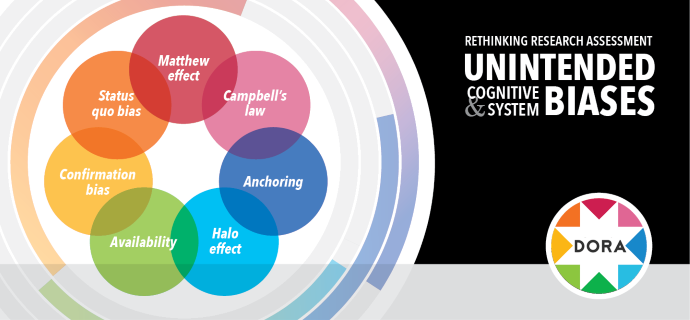

In part one of our series we showed how objective comparisons are not equitable. In our second part of this series we showed how individual data points can accidentally distract from the whole. Now in part 3 we explore how we gauge value by association.

While we often give individual data points too much weight, we also face a related, but distinct, tendency to see patterns where they may not exist, or to apply less-than-sound mental models to define the relationships between items. This means that our interpretations of future likelihoods, personal abilities, and relative importance are often skewed, which in turn can impact how we judge risk or prioritize options.

Not surprisingly, the Halo effect also contributes to this tendency, as seen in cases where highly rated or prominent institutions and journals (and individuals associated with them) receive the benefit of the doubt based on reputation. While this associative property can feel like a useful shortcut, it can cause decision-makers to overlook or override important data that should give us pause. For example, noting that an applicant shares one’s alma mater or trained under one’s former mentor might unfairly bolster their reputation based on factors that have little to do with the quality of their own work.

Another classic behavioraleconomics concept known as Availability is equally relevant. This describes our tendency to fall back on or place a higher weight on anecdotal, top-of-mind, or easily recalled data when making choices. In doing so, availability reduces our power to be fair-minded and equitable, because we end up dismissing other important evidence and missing the bigger picture. Availability can occur when individual or memorable anecdotes are prioritized in academic assessment, like overweighting a single experience or leaning too heavily on someone’s anecdotal recollection to inform a hiring decision. It can also lead to over-valuing recent data, like getting a well-known grant, instead of pursuing a fuller picture of scholarly productivity that would yield a more well-rounded decision.

What can institutions do?

Structured information gathering. These tendencies are more likely to occur when there’s no formal mechanism to gather data, increasing the likelihood individual memories or perceptions will dominate judgment and decision-making. The use of structured formats, like interview protocols and narrative format CVs, can keep decision-makers focused on agreed-upon qualities rather than on the vagaries of individual interactions and reflections and also ensure greater consistency of information across candidates.

Force long-term thinking. Short-term thinking tends to come more naturally than planning for the future, which means that the attributes we consider important are often more oriented toward immediacy over the longer term. Explicitly articulating and considering longitudinal values and goals, in addition to short-term needs, can help decision-makers concretize the potential outcomes, both pro and con, of decisions.

Contextualizing narratives. Traditional CVs are not known for their ability to demonstrate the big picture. Asking applicants to provide supplemental narratives that highlight and articulate their most meaningful contributions can convert commonly used shortcut characteristics for quality and productivity into more human form. This can re-center the conversation around research impact that extends beyond citations and academic circles to include demonstrable real-world change and improved outcomes, and provide concrete definition to otherwise vague terms like “world-class” and “significant contribution.”

In our final installment next week, we’ll call out how incumbent processes and perceptions have the advantage.

To encourage the adoption of more equitable hiring, and RPT processes, the authors are collaborating on a series of tools for DORA to assist institutions in experimenting with new processes, indicators, and principles. Available here.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephen Curry for very helpful comments. We also thank Stephen, Olivia Rissland and Stuart King for and the accompanying briefing document on the DORA webpage.